By Zachariah Chan, HealthServe intern & University of Hong Kong’s (HKU) School of Public Health student

Perspectives from a “foreign worker”

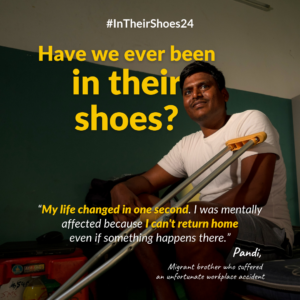

Low-wage migrant workers handle the brunt of labour-intensive jobs in Singapore. Yet, they do not seem to receive proportional healthcare access and compensation for the high-risk nature of their work. When there is a need to seek treatment, complications often arise due to their priority in holding on to a job that allows them to send money to their loved ones – what drew them to leave their homes to build ours, in the first place.

As someone from a foreign country, it has been quite eye-opening to witness the various types of work that our migrant brothers here do, the environment they live in, and the difficulties they face.

Poor health – often resulting from their working and living conditions – and finding accessible and affordable healthcare can prove to be stressful for migrant workers. Unlike local residents, migrant workers are subject to different policies and procedures when it comes to accessing healthcare. In the case of a work injury, there’s the Work Injury Compensation Act (WICA) to aid them, but many of them face difficulties due to their lack of knowledge and access to resources, including the right people to consult. This is compounded by other challenges they grapple with working under low income and the Special Pass – a pass assigned to foreigners that allows them to stay in Singapore while assisting in investigations, work injury claims or salary claims; but does not allow them to work.

Working in major industries such as construction, marine shipyard, and process (CMP), these migrant workers, who make up more than 15% of Singapore’s labour force, form the backbone of Singapore’s development and are an essential part of the economy. Low-wage migrant workers handle the brunt of labour-intensive jobs in Singapore. Yet, they do not seem to receive proportional healthcare access and compensation for the high-risk nature of their work. When there is a need to seek treatment, complications often arise due to their priority in holding on to a job, significantly higher costs of living in Singapore, and the lack of appropriate communication channels here. From my internship experience in HealthServe’s clinic and casework teams, I have observed that workers often expressed dissatisfaction in two areas – the price of their company doctors, and the difficulty of finding doctors who understand their needs.

The Singapore government’s recent introduction of the mandatory Primary Care Plan (PCP) for migrant workers is a move that HealthServe, as the only local medical NGO for migrant workers, has advocated for years. While this development is undoubtedly commendable, the unfortunate reality is that many workers still face language barriers, a lack of employer support as well as access to mental health support – when the migrant population’s stressors are aplenty! Awareness and education of their rights under the new PCP is another challenge that will take time to address.

Some migrant brothers I met were also afraid of their supervisors as they feared repatriation, or that they would be allocated a Special Pass upon knowing that they were sick. This carries an unsettling implication that there may always remain errant employers who discourage their migrant employees from seeking timely healthcare – a universal right that everyone, low-wage migrant workers included, should be entitled to. Having said that, I must qualify that many employers I have met during my time at HealthServe have generally been supportive and played an active role in improving the health of ill workers – which I found to be very heartening.

On another hand, the problem of poor peer-to-peer support on the ground was clearly evident. Could it be an issue of information accessibility from the authorities, or lacking company infrastructure? To me, the answer probably includes a mix of both and underlines insufficient understanding and effective communication with our migrant friends. In this regard, HealthServe’s Mental Health team has introduced education programmes such as the Peer Support Leader (PSL) training that equips migrant workers with skills to care for themselves and others. Aimed at strengthening peer support from the very source and in a community-based approach, the high referral rate from PSLs I have met is testament to the programme’s efficacy.

Dignity, mental health, and holistic wellbeing

Migrant workers in the CMP sector are often not regarded with much respect, given the stereotype of their jobs as “low-education”. I have spoken to quite a number of migrant workers who have university degrees and cannot imagine their frustration living amid such stigma. This stigma, compounded by the other mentioned stressors and poor awareness of mental health and needed crisis intervention could very well increase the risk of suicide and self-harm. During my time in HealthServe, I have supported clinic services that tended to workers’ physical health, and also assisted migrant brothers in their mental troubles in the casework team. These problems ranged from enquiries on permit status to financial troubles and more complex issues involving WICA. Just as how poor physical health can lead to poor mental health, the inverse can be true in this case – showing the need for the recognition of mental health as an essential part of one’s wellbeing. Compared to conventional GP clinics, HealthServe’s services address both patients’ physical and mental health – demonstrating the value of understanding our migrant brothers beyond their physical conditions, extending towards the environmental risk factors and difficulties they face in their daily routines. One’s mental health is not just tied to one’s socialisation, but carries community-wide effects.

By not addressing the holistic wellbeing of our migrant brothers, we are neglecting a significant population that has contributed much to Singapore’s economy and cultural diversity. Without addressing their social determinants of health, we wouldn’t have a socially inclusive environment where our migrant workers maintain a state of physical and most importantly, mental wellbeing.

With policy developments such as the government-mandated health insurance for migrant workers, the future looks optimistic, but I find that there remains more room for our migrant brothers to be seen, recognised, and integrated with the rest of Singapore. NGOs can only continue the push for continued support for our migrant friends – it is when the government, employers, local communities and other stakeholders come together to tackle systemic issues in different social spheres, that we will finally start steering away from band-aid relief and come closer to addressing the root causes of the social injustice low-wage migrant workers face.